One of the major concerns most animals deal with is the means by which to discover their way around there —for instance, to know where a specific food source is located and how to reach there from their current location, or which is a safe route towards home to keep away from a predator. Such spatial learning may cover just the  exceptionally limited bounds of an animal’s home range or region, or it might grasp a migratory route of a few hundreds or even thousands of kilo meters. There are instances where these navigational abilities don’t require extraordinary spatial skills still there are exemplary moments that reveal unbelievable spatial abilities of animals that amaze human eye and that prompt the learners of animal cognition to conduct extensive research to find out the spatial intelligence of different non-human animals.

exceptionally limited bounds of an animal’s home range or region, or it might grasp a migratory route of a few hundreds or even thousands of kilo meters. There are instances where these navigational abilities don’t require extraordinary spatial skills still there are exemplary moments that reveal unbelievable spatial abilities of animals that amaze human eye and that prompt the learners of animal cognition to conduct extensive research to find out the spatial intelligence of different non-human animals.

One such exemplary moment is the navigation of the starling bird.

The amazing swirling movements of a starling flock seem like smoke in the air, a wonderful phenomenon of nature that delights its observers. This is why the group of starlings flying together is not referred to as merely a flock rather this group swirling wonderfully is named as murmuration & phenomenon itself is also called murmuration, a word that best describes the collective sound of thousands of pairs of wings.

The amazing swirling movements of a starling flock seem like smoke in the air, a wonderful phenomenon of nature that delights its observers. This is why the group of starlings flying together is not referred to as merely a flock rather this group swirling wonderfully is named as murmuration & phenomenon itself is also called murmuration, a word that best describes the collective sound of thousands of pairs of wings.

Murmuration enables these birds to prevent from predators, it confuses predators & makes it difficult for them to single out prey. Starlings making zigzag patterns, waving moments in turn making dark bands misperceive predators. As wavy structures are considered to be the strongest building structures because wavy patterns provide arch support so is the case with the wavy movement patterns of starling flock, that it proves a strongest way to prevent from predators, think this beautiful phenomenon this way.

So, the question is how thousands of starlings make such coordinated moments during their flight, how they are able to make twist and turns in a moment’s notice, how birds flying at one side of the murmuration coordinate to the birds flying at the opposite side of murmuration?

Experts rely on science to answer these questions related to amazing coordination of starling birds. Most of them say that each starling follows its neighbor, it turns when its neighbor turns as they are close enough and can see each other but the question is how hundreds of thousands of starlings communicate and decide directions simultaneously?

In 2013 George F. Young (researcher at Princeton University, New Jersey USA) & his colleagues tried to investigate what exactly happens during murmuration where a remarkably large number of birds maintain cohesion with an uncertain environment & without any noisy communication.

He already knew that each individual starling coordinates with a fixed number of its neighbors in the flock irrespective of the density of the flock i.e. one starling communicates to its successive seven starlings, second staling communicates to its seven successive starlings and so on. So what was the contribution of George? His contribution was to highlight: “when murmuring starlings sense uncertainty, their interaction with seven neighbors optimizes the balance between group cohesiveness and individual effort”.

Its not only the murmuration that compels human beings to confess the spatial abilities of starling bird but also their migration over thousands of miles that they undertake to protect themselves from extremely cold weather.

For instance, starlings that breed around the Baltic Sea fly Southwest in pre-winter to winter in Southern England, northern France, and Belgium. In one experiment they were caught during this pre-winter migration and dropped in Switzerland (somewhere in the range of 500 miles south of their ordinary course), but they did not stay in Switzerland anymore after forcefully dropped there. From Switzerland they flew back to northern France and Belgium—despite the fact that they had apparently never flown over any part of this route previously. Although young starlings, who migrated for the first time, flew Southwest from Switzerland and stayed in Southern France or Northern Spain. They had an accurate compass that disclosed to them which territory was Southwest; what they needed was any information on the spatial connection between their current area in Switzerland and their desired area of Northern France. Young starlings could not return back to their desired location, this experiment concluded that spatial abilities are learned by experience and animals evolve spatial cognition as they grow over time

Experiments on sea creatures also revealed that they also got extraordinary spatial skills. For example, salmon migrate from the sea to their origins i.e. the stream wherein they were brought forth; Swallows migrate back to similar home destinations in Northern Europe each spring from wintering in Southern Africa. These findings  prompted students of animal cognition to conduct a series of researches, most famous of which is an experiment related to a sea bird Manx Shear. A Manx Shearwater was taken in a plane from its hatched site on the island of Skokholm, off south Wales, to Boston, Mass. It came back to Skokholm by 13th day of being dropped off in Boston; distance between these two places is almost 3050 miles. Similarly, a gooney bird flew from a dropped off site in the Philippines to its home in Midway Island, a journey of 4,120 miles, in 32 days.

prompted students of animal cognition to conduct a series of researches, most famous of which is an experiment related to a sea bird Manx Shear. A Manx Shearwater was taken in a plane from its hatched site on the island of Skokholm, off south Wales, to Boston, Mass. It came back to Skokholm by 13th day of being dropped off in Boston; distance between these two places is almost 3050 miles. Similarly, a gooney bird flew from a dropped off site in the Philippines to its home in Midway Island, a journey of 4,120 miles, in 32 days.

How do these creatures explore across such significant stretches? Various signs have been explained in various examples. Close to home, creatures most likely depend on neighborhood signals that are different from their own habitat. For instance, tests show that salmon recognize their home streams based on smell, in spite of the fact that this sense can scarcely become an integral factor while the fish are swimming in the vast sea. Different examinations have shown that diurnal fowls utilize visual data got from the situation of the Sun, while those that move around evening time depend on the example of the stars. There have been a few recommendations that specific long-run migrators are delicate to the Earth’s attractive powers; affectability to hear-able signals have likewise been proposed at times.

fact that this sense can scarcely become an integral factor while the fish are swimming in the vast sea. Different examinations have shown that diurnal fowls utilize visual data got from the situation of the Sun, while those that move around evening time depend on the example of the stars. There have been a few recommendations that specific long-run migrators are delicate to the Earth’s attractive powers; affectability to hear-able signals have likewise been proposed at times.

At instances these birds are prepared by dropping them off from surroundings quite far away from their hatched sites. Exactly what the pigeons realize on these preparation flights isn’t totally clear. To some extent, they clearly get familiar with the visual tourist spots promptly encompassing the home space, however test proof recommends that they utilize certain milestones. When some preparation has been given, a pigeon can be taken 100 miles or more toward any path from home, and it will, inside a couple of moments of its being dropped off, begin flying back towards home way.

One general class of hypothesis on homing conduct proposes that the pigeon recognizes the inconsistency between the impulses felt at release site and the impulses felt at its own hatched site, and it at that point flies such a way as to decrease this inconsistency. Various variants of this hypothesis claim to various arrangements  of impulses that may be utilized to manage the pigeon home. Similarly, Sun’s position in the sky together with an inside clock of pigeon was regarded as its navigation tool. But later, research proved these two factors are not really the navigational tool for the homing pigeons. In one experiment pigeons were kept in a room and they were exposed to sun for very little time of the day and they were misperceived by allowing them to see the sun from mirrors showing height of the sun higher or lower than its original height. After few days they were released from a quite far location but the pigeons started to fly towards their home in the right direction. This proved that they don’t depend on height of the sun to navigate

of impulses that may be utilized to manage the pigeon home. Similarly, Sun’s position in the sky together with an inside clock of pigeon was regarded as its navigation tool. But later, research proved these two factors are not really the navigational tool for the homing pigeons. In one experiment pigeons were kept in a room and they were exposed to sun for very little time of the day and they were misperceived by allowing them to see the sun from mirrors showing height of the sun higher or lower than its original height. After few days they were released from a quite far location but the pigeons started to fly towards their home in the right direction. This proved that they don’t depend on height of the sun to navigate

In another experiment, internal clock of the pigeons was tried to alter by keeping them in a laboratory for many days; away from sun light and exposed to artificial lights such that at midnight lights were turned on and at noon lights were turned off. After several days at 6am when they were released 50 miles away from their home in the west, the internal clock of their body indicated that it must be noon at their homing location and therefore they must fly towards west, so the birds starting flying towards west instead of south. This experiment concluded that internal clock of the pigeon really plays a role in its way finding ability. So, pigeons depend on their own compass to navigate but there must be a map that allows them to navigate correctly. It’s still mysterious which map it uses

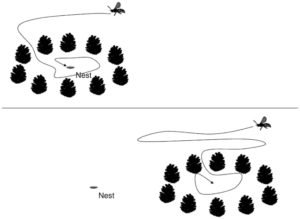

While talking about spatial abilities of non-human animals it’s not possible to conclude without discussing the  spatial memory of honey bees. Honey bees navigate according to a map like spatial memory. They observe the landmarks between their hive and the food source, their short term memory is helpful in their way finding. Short-term memory plays a significant role around 4-5 days, after which they gradually forget what they observed, and at day 6, 7, 8 short-term spatial memory fades away. In one experiment, at day 9th honey bees completely forgot to find their way towards their hive.

spatial memory of honey bees. Honey bees navigate according to a map like spatial memory. They observe the landmarks between their hive and the food source, their short term memory is helpful in their way finding. Short-term memory plays a significant role around 4-5 days, after which they gradually forget what they observed, and at day 6, 7, 8 short-term spatial memory fades away. In one experiment, at day 9th honey bees completely forgot to find their way towards their hive.

These are few instances of animal’s spatial skills or spatial intelligence. In fact, way finding ability of Chimpanzees and other apes, elephants, rats and many other animals, birds and insects is indispensable for their survival.

So, if today we as human beings share spatial skills with non-human animals then hundreds of millions years ago, ancestors of non-humans and humans split a part to grow the different branches of the tree of life.

Spatial intelligence is the ability to perceive the visual world precisely; ability to modify and transform one’s initial perceptions and ability to create mental images. It’s the ability to imagine world in three dimensions. Architects, sailors, painters, pilots have high levels of spatial intelligence. People with this type of intelligence love to imagine fictitious things, daydream, draw images on paper, correlate various objects, find similarities and differences between shapes of different objects, closely observe structures. In fact, they are artist by nature.

Spatial intelligence is not unique to latest generations of human beings, in fact, study of ancient civilizations reveal that they were far more spatially intelligent than that of today’s generations.

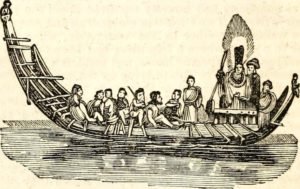

Ancient Polynesians were famous for long distance voyaging. They voyaged in the deep oceans to establish large colonies of people, to deal with war or famine plus they were eager to explore the adventure of discovery. They had sophisticated vessels and navigation system based on observations of the stars, ocean swells, flight patterns of birds and other natural signs that helped them to navigate across deep seas and mighty oceans. In reality, ancient art of long distance way finding has been lost to the ancient Polynesian societies of the Pacific.

Understanding origins and evolution of spatial abilities helps us in effective communication of spatial knowledge, either face-to-face, by publishing or by sign-posting that eases the journey of man around the world with no or little prior travel history. Besides spatial skills used in building cities, roads, and transportation systems designs an environment in which everyone may navigate easily. Spatial intelligence is actually blend of other types of intelligence, if you have musical and linguistic intelligence, you may be able to develop spatial skills.

Facebook : Think Different Nation

Instagram : Think Different Nation

Twitter : @TDN_Podcast